Henri-Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa, was born on November 24th 1864 at Albi in the South of France. His father was a count. The

Lautrec's family records going back to 1196. He was born normal, a pleasant child with a bright eye and happy laugh. But soon illness overcome him and a strange bone disease destroyed his figure after he fell and broke his legs. He became a dwarf.

Henri was a born draftsman, already as a child a great maker of lines and form. One has but to see his early sketch books, the drawings on his letters during his teens, to realize he saw everything as material for his pen or pencil. Even his paintings were mostly drawn and colored, usually on cardboard, rather than painted with full values of pigments. Almost all his life he drew his paintings with bold lines or little dashing strokes, blending his forms together with the eye of a graphic artist first. It is his patterns, his scenes, his skills with the object we remember best, not the paint or the color.

Lautrec's first teacher in 1880 was

René Princeteau, a fine painter of horses and soldiers, and he taught Lautrec so well that we sense in this boy's work a craftsmanship and a virtuosity in drawing that already suggests a master. His horses curve their necks and gallop, his hounds spring into the air, every pencil line of rider or carriage is alive and active. The essence of an artist is that he should be articulate a critic had written.

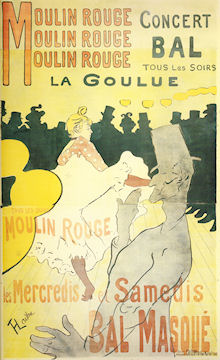

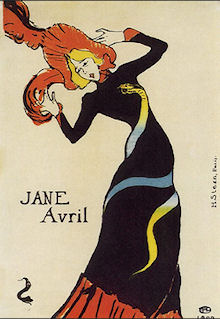

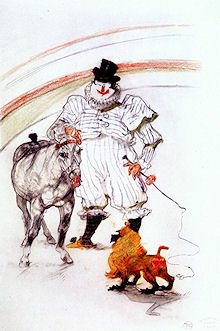

Few took him seriously a a painter. His first fame cane from his posters and from his lithograph drawings on the stone.; Cha-U-Kao the clown, Loie Fuller, Artistide Brant. Lautrec was a true graphic artist, saying what he had to say of the Paris of his time, its night life, the flaring gaslights outlining diners and dancers, courtesans and pleasure seekers. in poster after poster he alerted the town, and in a series of prints het captured the raddled flesh of the great actors, the strange mouths and noses of the singers, the features of the woman who served with bodies and gestures to excite an ear. The quadrille at the Moulin Rouge, La Coulue dancing, the Cirque Fernando.

The city took on color with Lautrec's posters of Le Divan Japonais, and Les Ambassadeurs. He exhibited his pictures of Montmartre life and made the mastery series of drawings of the green-eyed, long-nosed, black-gloved Yvette Guilbert, who called him: Petit monstre une horreur.

Always drawing music halls, dance dives, theatres, and the streets he passed through the 90's and came near to the 20th century. He agreed with the critic who said: To let oneself go, that is what art is always aiming at.

His mind and body deteriorated by drink, he was locked up in the Saint James Clinic at Neuilly in 1899. I am shut up and everything that is shut up dies, he said. To prove he was still capable of thinking and working he created, from memory, one of his best series of drawings: Le Cirque. This and the press campaign of his friends got his release. But the end was near. There was no way fully back. Only his drawings kept coming from the hand that had nearly reached its grasp of a pencil. The critic Ruskin wrote: The art of drawing is of more real importance than that of writing.

Lautrec asked to be taken to his mother at the Chateau de Malromé. Crippled, ugly, worn down by a hand-lived life, he sat in the sun and she held his hands. With his mother near him he died on September 9, 1901 at the age of 36. Someone who present at the end said: He watched everything but hardly talked at all. The look in his eyed had changed and he could not bring himself to laugh.

Lautrec liked to work on a cardboard. The surface yellowed quickly to grain on which with a brush he drew rapidly, trying out ideas and then throwing on some white and adding a color tone here and there. These were drawings rather than paintings and are among his most pleasing works. The board has browned and its surface has absorbed the turpentine and the oil, so that the pattern is bolder than ever and the drawing binds it together.

Much of his best work is found in the grease crayon drawings he did on the lithographer's stone. Drawing directly on the cold surface, his every touch was personal, vital and alert. The prints made from his drawings are among the glories of draftsmanship. The influence of Japanese prints shows in its placement on the paper, the neglect of shadow, of banal detail. In following the masters of Japanese prints Lautrec too caught the feeling moment, what they called: the floating world and a new way gave us pictures from a viewpoint we would not have seen without their help.

Toulouse-Lautrec's drawings do not distort as much as later moderns did their subjects. But he does have a personal viewpoint, a gem-hard ironic bite. His people are bared to us at their most intimate, at their most gay. He is an artist who always aware of the skull beneath the skin. He hides little from us, he has no moral message for us, only the futility of human effort and human despair. He never preaches, never sinks into popular cant. Some of his subject matter is strong, as in his mocking erotic scenes. Taken as a whole his vast collection of drawings picture for us an era with the skill and nuances of a great novelist, from Chocolat Dancing to Le Grand Lodge.

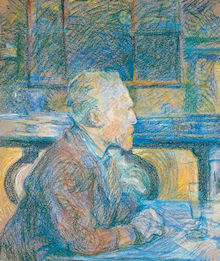

Only his people matter. He never bothered much with landscape. it was there but he had no interest in it. He influenced

Picasso, and the young Spaniard came to Paris o meet him, only to find him already dead. Lautrec's subjects of the fin du siècle were the themes of many young modern artists. The artist Moreau told his pupils: Go study a figure by Lautrec, done entirely in absinthe. The little artist would have liked that recommendation and its reference to his habits.

> Read more

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Biography of a many-sided artist by Musée Toulouse-Lautrec